Watch this

http://www.bbc.co.uk/programmes/p01sx758

Journalist Paul Salopek embarks on a seven-year global trek from Africa to Tierra Del Fuego, following in the footsteps of our restless forebears.

See National Geographic Magazine December 2013

Dezeen

FAT architects announce

studio closure

News: London architecture office FAT has announced that it will shut down its studio next summer, after “exploring the potential of the projects as much as possible”.

FAT directors Sean Griffiths, Charles Holland and Sam Jacob, who became famous for combining Postmodernist architecture with playful iconography, plan to end their 23-year-old practice with the completion of two major projects – the curation of the British Pavilion at the Venice Architecture Biennale 2014 and a house inspired by fairytales that they are working on with artist Grayson Perry for the Living Architecture series of holiday homes.

“We feel like we’ve explored the potential of the projects as much as possible,” Jacob told Dezeen. “We don’t want to end up like many architects do, flogging the same dead horse. We think it’s best to go out on a high.”

“In lots of ways FAT has been more like a band than a traditional architecture office,” he added. “We wanted to finish it in a way that’s coherent and makes sense.”

FAT started in the mid 1990s as a collective of architects, artists and film makers, before going on to complete projects such as the Blue House in London’s Hackney, the BBC Drama Production Village in Cardiff andthe Community In A Cube (CIAC) in Middlesborough.

“What we’re doing is saying there’ll be two more projects,” said Jacob. “We think this is really the completion of the FAT project which began many years ago, with no intention that we were starting an architecture office and the ‘glittering careers’ we would have.”

After completing the two final projects, the three partners plan to “let the dust settle”, but will continue to work within the architecture and design industry. Jacob is currently also a columnist for Dezeen.

Here’s the full announcement from FAT:

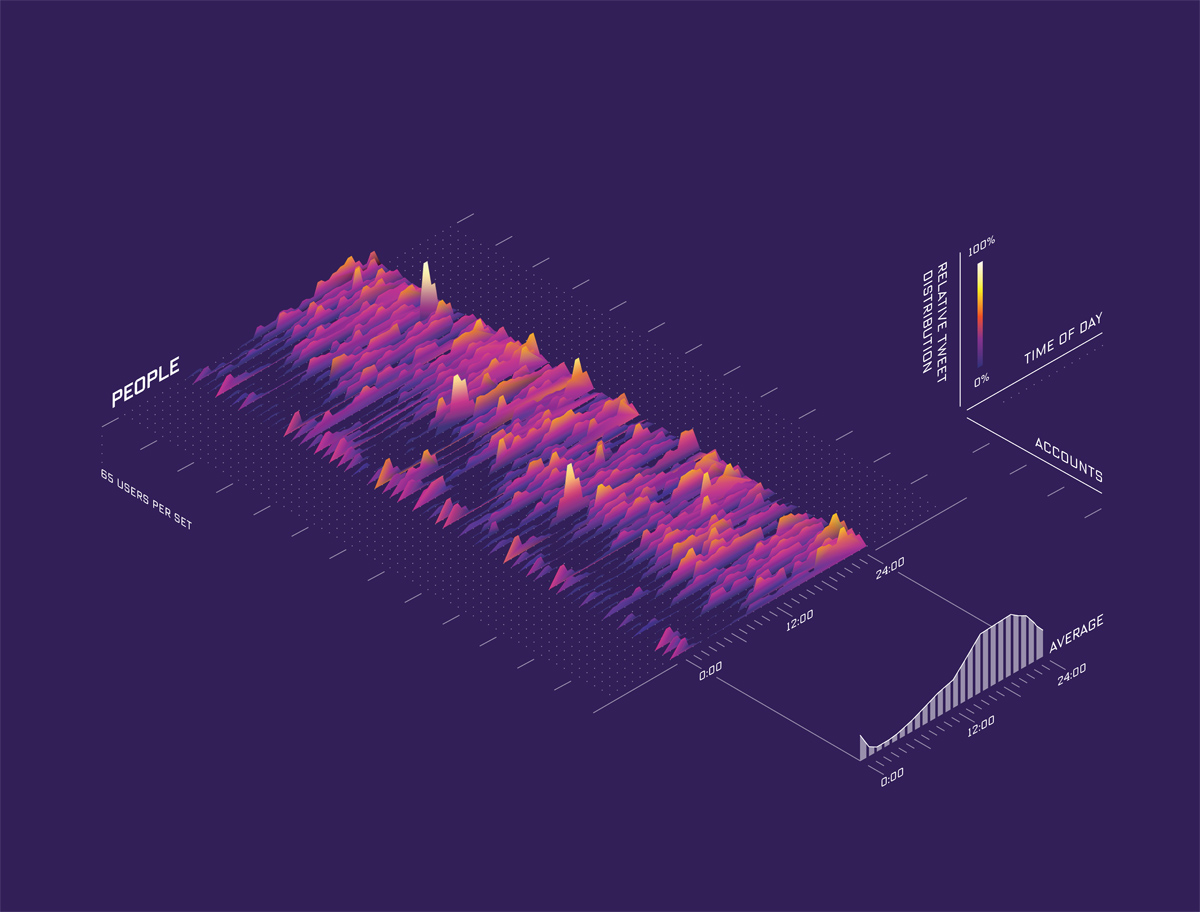

New Algorithm Can Spot the Bots in Your Twitter Feed Wired Magazine

- BY LEE SIMMONS

You know Twitter spam when you see it—but wouldn’t it be nice if you didn’t have to see it?

Unfortunately, email-style filters, which analyze message contents, are of little help. Due to the rigors of 140-character communication, even legitimate tweets tend to read like Nigerian phishing scams, while the hucksters often hide their pitches in links. So Twitter simply puts the onus on users to report offending accounts.

But a fascinating recent study from Imperial College London suggests a new approach. Borrowing some tricks from computational neuroscience, coauthors Gabriela Tavares and Aldo Faisal have come up with an algorithm that can tell—with 85 percent accuracy—whether a Twitter account is home to a bot or (worse) a corporate shill instead of a regular person.

It’s all in the timing. By analyzing the timestamps on 165,000 tweets, the researchers found that these three user types—individuals, companies, and robots—have very distinct activity patterns. Think of it as temporal fingerprinting. The approach could eventually be used to create more effective filters for all kinds of social networks.

Sketchy information: illustration as a tool of understanding

Symposium considers drawing’s role in refining and communicating knowledge, from geology to surgery to unicorns

Sketches of reality: illustrations can communicate information but can also be used to mislead

The role of illustration as an “active means of interrogating, investigating and communicating knowledge and understanding” came under scrutiny at an international symposium in Oxford last week.

Paul Smith, director of the Oxford University Museum of Natural History (which hosted the event), presented a paper on Charles Lapworth, “one of the great unsung heroes of Victorian science”.

Even now, he observed, geology is a discipline where “primary data-gathering is done through illustration, boiling down the landscape into a testable hypothesis”. In Lapworth’s 1882 notebooks, it’s possible to see him “trying to get a feel for the patterns in the landscape” and developing a radical new theory about the formation of the Scottish Highlands solely through sketches and maps with only an occasional few words of text.

Illustration can play an equally important role in medicine. Francis Wells, a cardiothoracic surgeon who is also an associate lecturer at the University of Cambridge, described how his own interest in draughtsmanship, and particularly the anatomical drawings of Leonardo da Vinci, had provided crucial insights into the progress of a disease affecting the valves in the human heart.

Uta Kornmeier, a researcher at the Center for Literary and Cultural Research in Berlin, recalled being approached by a surgeon who did not consider himself an artist but was required “literally to sculpt the bones of babies affected by craniosynostosis into a different shape”.

The very idea of “reconstruction”, she went on, “implies a correct shape, though what that means is not discussed in the medical literature”. Surgical textbooks offer little guidance on the shape of a “normal” skull, and even anatomy textbooks have little to say about babies’ skulls.

Adopting a more historical approach, Martin Kemp, emeritus professor of the history of art at the University of Oxford, examined the “rhetorics of the real”: the visual tricks that artists use to convince viewers to take on trust what they are shown. In the past, he argued, “it wasn’t daft to believe in unicorns”, since people could cite seemingly reliable sources and pictures classifying a number of subspecies. Equally important were the techniques of what Leonardo called “combinatory imagination”, which can be highly effective in producing “convincing monsters”.

Designer Johnny Hardstaff, meanwhile, turned to “future graphic languages” as he described three short films he made for director Ridley Scott to address the question of how “humanity might broadcast its existence to alien life”.

Science, Imagination and the Illustration of Knowledge was the fourth International Illustration Symposium organised by the Illustration Research Network, supported by the University of the Arts London and Camberwell Press. The third symposium was held at the Ethnographic Museum in Cracow, Poland in 2012. Material from that event features prominently in a peer-reviewed publication, the Journal of Illustration, which was launched by Intellect at this year’s symposium.

matthew.reisz@tsleducation.com

device under his skin

News: biohacker Tim Cannon has taken wearable technology to a new extreme by implanting a device into his arm so he can monitor his biometric data on a tablet.

Cannon had the body-monitoring device inserted under the skin on his left forearm to track changes in his body temperature.

Built by his company Grindhouse Wetware, the Circadia 1.0 contains a computer chip within a sealed box about the size of a pack of cards and is powered by a battery that can be wirelessly charged.

![]()

Realtime readings of Cannon’s body temperature are transmitted from the chip to his Android-powered device via Bluetooth.

He is able to monitor fluctuations and notice if he is getting a fever, as well as look back at recorded data to find patterns he can use to adjust his lifestyle and help keep him healthy.

“I think that our environment should listen more accurately and more intuitively to what’s happening in our body,” Cannon explained to tech blog Motherboard. “So if, for example, I’ve had a stressful day, the Circadia will communicate that to my house and will prepare a nice relaxing atmosphere for when I get home: dim the lights, let in a hot bath.”

![]()

A fellow body modification enthusiast implanted the chip in Cannon’s arm without anaesthetics, as doctors aren’t authorised to insert non-medical devices.

LEDs built into the case flash when the device connects to the tablet, lighting up the tattoo on Cannon’s forearm.

The Circadia 1.0 will be available to buy in the next few months at an estimated cost of $500 (£314). Cannon has reportedly already been able to make a smaller version the device and plans to incorporate a pulse monitor.

By embedding the technology into his body, Cannon has taken a leap forward from removable body-monitoring devices worn around the wrist such as the Nike+ FuelBand and Jawbone’s Up, or concept for the flexible electronic circuits that stick directly to the skin. Dezeen editor-in-chief Marcus Fairs discussed how wearable technology will “transform our understanding of ourselves” in his Opinion column earlier this year.

From http://www.theguardian.com/books/2013/oct/15/neil-gaiman-future-libraries-reading-daydreaming

Neil Gaiman: Why our future depends on libraries, reading and daydreaming

A lecture explaining why using our imaginations, and providing for others to use theirs, is an obligation for all citizens

It’s important for people to tell you what side they are on and why, and whether they might be biased. A declaration of members’ interests, of a sort. So, I am going to be talking to you about reading. I’m going to tell you that libraries are important. I’m going to suggest that reading fiction, that reading for pleasure, is one of the most important things one can do. I’m going to make an impassioned plea for people to understand what libraries and librarians are, and to preserve both of these things.

And I am biased, obviously and enormously: I’m an author, often an author of fiction. I write for children and for adults. For about 30 years I have been earning my living though my words, mostly by making things up and writing them down. It is obviously in my interest for people to read, for them to read fiction, for libraries and librarians to exist and help foster a love of reading and places in which reading can occur.

So I’m biased as a writer. But I am much, much more biased as a reader. And I am even more biased as a British citizen.

And I’m here giving this talk tonight, under the auspices of the Reading Agency: a charity whose mission is to give everyone an equal chance in life by helping people become confident and enthusiastic readers. Which supports literacy programs, and libraries and individuals and nakedly and wantonly encourages the act of reading. Because, they tell us, everything changes when we read.

And it’s that change, and that act of reading that I’m here to talk about tonight. I want to talk about what reading does. What it’s good for.

I was once in New York, and I listened to a talk about the building of private prisons – a huge growth industry in America. The prison industry needs to plan its future growth – how many cells are they going to need? How many prisoners are there going to be, 15 years from now? And they found they could predict it very easily, using a pretty simple algorithm, based on asking what percentage of 10 and 11-year-olds couldn’t read. And certainly couldn’t read for pleasure.

It’s not one to one: you can’t say that a literate society has no criminality. But there are very real correlations.

And I think some of those correlations, the simplest, come from something very simple. Literate people read fiction.

Fiction has two uses. Firstly, it’s a gateway drug to reading. The drive to know what happens next, to want to turn the page, the need to keep going, even if it’s hard, because someone’s in trouble and you have to know how it’s all going to end … that’s a very real drive. And it forces you to learn new words, to think new thoughts, to keep going. To discover that reading per se is pleasurable. Once you learn that, you’re on the road to reading everything. And reading is key. There were noises made briefly, a few years ago, about the idea that we were living in a post-literate world, in which the ability to make sense out of written words was somehow redundant, but those days are gone: words are more important than they ever were: we navigate the world with words, and as the world slips onto the web, we need to follow, to communicate and to comprehend what we are reading. People who cannot understand each other cannot exchange ideas, cannot communicate, and translation programs only go so far.

The simplest way to make sure that we raise literate children is to teach them to read, and to show them that reading is a pleasurable activity. And that means, at its simplest, finding books that they enjoy, giving them access to those books, and letting them read them.

I don’t think there is such a thing as a bad book for children. Every now and again it becomes fashionable among some adults to point at a subset of children’s books, a genre, perhaps, or an author, and to declare them bad books, books that children should be stopped from reading. I’ve seen it happen over and over; Enid Blyton was declared a bad author, so was RL Stine, so were dozens of others. Comics have been decried as fostering illiteracy.

No such thing as a bad writer… Enid Blyton’s Famous Five. Photograph: Greg Balfour Evans/Alamy

No such thing as a bad writer… Enid Blyton’s Famous Five. Photograph: Greg Balfour Evans/Alamy

It’s tosh. It’s snobbery and it’s foolishness. There are no bad authors for children, that children like and want to read and seek out, because every child is different. They can find the stories they need to, and they bring themselves to stories. A hackneyed, worn-out idea isn’t hackneyed and worn out to them. This is the first time the child has encountered it. Do not discourage children from reading because you feel they are reading the wrong thing. Fiction you do not like is a route to other books you may prefer. And not everyone has the same taste as you.

Well-meaning adults can easily destroy a child’s love of reading: stop them reading what they enjoy, or give them worthy-but-dull books that you like, the 21st-century equivalents of Victorian “improving” literature. You’ll wind up with a generation convinced that reading is uncool and worse, unpleasant.

We need our children to get onto the reading ladder: anything that they enjoy reading will move them up, rung by rung, into literacy. (Also, do not do what this author did when his 11-year-old daughter was into RL Stine, which is to go and get a copy of Stephen King’s Carrie, saying if you liked those you’ll love this! Holly read nothing but safe stories of settlers on prairies for the rest of her teenage years, and still glares at me when Stephen King’s name is mentioned.)

And the second thing fiction does is to build empathy. When you watch TV or see a film, you are looking at things happening to other people. Prose fiction is something you build up from 26 letters and a handful of punctuation marks, and you, and you alone, using your imagination, create a world and people it and look out through other eyes. You get to feel things, visit places and worlds you would never otherwise know. You learn that everyone else out there is a me, as well. You’re being someone else, and when you return to your own world, you’re going to be slightly changed.

Empathy is a tool for building people into groups, for allowing us to function as more than self-obsessed individuals.

You’re also finding out something as you read vitally important for making your way in the world. And it’s this:

The world doesn’t have to be like this. Things can be different.

I was in China in 2007, at the first party-approved science fiction andfantasy convention in Chinese history. And at one point I took a top official aside and asked him Why? SF had been disapproved of for a long time. What had changed?

It’s simple, he told me. The Chinese were brilliant at making things if other people brought them the plans. But they did not innovate and they did not invent. They did not imagine. So they sent a delegation to the US, to Apple, to Microsoft, to Google, and they asked the people there who were inventing the future about themselves. And they found that all of them had read science fiction when they were boys or girls.

Fiction can show you a different world. It can take you somewhere you’ve never been. Once you’ve visited other worlds, like those who ate fairy fruit, you can never be entirely content with the world that you grew up in. Discontent is a good thing: discontented people can modify and improve their worlds, leave them better, leave them different.

And while we’re on the subject, I’d like to say a few words about escapism. I hear the term bandied about as if it’s a bad thing. As if “escapist” fiction is a cheap opiate used by the muddled and the foolish and the deluded, and the only fiction that is worthy, for adults or for children, is mimetic fiction, mirroring the worst of the world the reader finds herself in.

If you were trapped in an impossible situation, in an unpleasant place, with people who meant you ill, and someone offered you a temporary escape, why wouldn’t you take it? And escapist fiction is just that: fiction that opens a door, shows the sunlight outside, gives you a place to go where you are in control, are with people you want to be with(and books are real places, make no mistake about that); and more importantly, during your escape, books can also give you knowledge about the world and your predicament, give you weapons, give you armour: real things you can take back into your prison. Skills and knowledge and tools you can use to escape for real.

As JRR Tolkien reminded us, the only people who inveigh against escape are jailers.

Tolkien’s illustration of Bilbo’s home, Bag End. Photograph: HarperCollinsAnother way to destroy a child’s love of reading, of course, is to make sure there are no books of any kind around. And to give them nowhere to read those books. I was lucky. I had an excellent local library growing up. I had the kind of parents who could be persuaded to drop me off in the library on their way to work in summer holidays, and the kind of librarians who did not mind a small, unaccompanied boy heading back into the children’s library every morning and working his way through the card catalogue, looking for books with ghosts or magic or rockets in them, looking for vampires or detectives or witches or wonders. And when I had finished reading the children’s’ library I began on the adult books.

Tolkien’s illustration of Bilbo’s home, Bag End. Photograph: HarperCollinsAnother way to destroy a child’s love of reading, of course, is to make sure there are no books of any kind around. And to give them nowhere to read those books. I was lucky. I had an excellent local library growing up. I had the kind of parents who could be persuaded to drop me off in the library on their way to work in summer holidays, and the kind of librarians who did not mind a small, unaccompanied boy heading back into the children’s library every morning and working his way through the card catalogue, looking for books with ghosts or magic or rockets in them, looking for vampires or detectives or witches or wonders. And when I had finished reading the children’s’ library I began on the adult books.

They were good librarians. They liked books and they liked the books being read. They taught me how to order books from other libraries on inter-library loans. They had no snobbery about anything I read. They just seemed to like that there was this wide-eyed little boy who loved to read, and would talk to me about the books I was reading, they would find me other books in a series, they would help. They treated me as another reader – nothing less or more – which meant they treated me with respect. I was not used to being treated with respect as an eight-year-old.

But libraries are about freedom. Freedom to read, freedom of ideas, freedom of communication. They are about education (which is not a process that finishes the day we leave school or university), about entertainment, about making safe spaces, and about access to information.

I worry that here in the 21st century people misunderstand what libraries are and the purpose of them. If you perceive a library as a shelf of books, it may seem antiquated or outdated in a world in which most, but not all, books in print exist digitally. But that is to miss the point fundamentally.

I think it has to do with nature of information. Information has value, and the right information has enormous value. For all of human history, we have lived in a time of information scarcity, and having the needed information was always important, and always worth something: when to plant crops, where to find things, maps and histories and stories – they were always good for a meal and company. Information was a valuable thing, and those who had it or could obtain it could charge for that service.

In the last few years, we’ve moved from an information-scarce economy to one driven by an information glut. According to Eric Schmidt of Google, every two days now the human race creates as much information as we did from the dawn of civilisation until 2003. That’s about five exobytes of data a day, for those of you keeping score. The challenge becomes, not finding that scarce plant growing in the desert, but finding a specific plant growing in a jungle. We are going to need help navigating that information to find the thing we actually need.

Photograph: AlamyLibraries are places that people go to for information. Books are only the tip of the information iceberg: they are there, and libraries can provide you freely and legally with books. More children are borrowing books from libraries than ever before – books of all kinds: paper and digital and audio. But libraries are also, for example, places that people, who may not have computers, who may not haveinternet connections, can go online without paying anything: hugely important when the way you find out about jobs, apply for jobs or apply for benefits is increasingly migrating exclusively online. Librarians can help these people navigate that world.

Photograph: AlamyLibraries are places that people go to for information. Books are only the tip of the information iceberg: they are there, and libraries can provide you freely and legally with books. More children are borrowing books from libraries than ever before – books of all kinds: paper and digital and audio. But libraries are also, for example, places that people, who may not have computers, who may not haveinternet connections, can go online without paying anything: hugely important when the way you find out about jobs, apply for jobs or apply for benefits is increasingly migrating exclusively online. Librarians can help these people navigate that world.

I do not believe that all books will or should migrate onto screens: as Douglas Adams once pointed out to me, more than 20 years before the Kindle turned up, a physical book is like a shark. Sharks are old: there were sharks in the ocean before the dinosaurs. And the reason there are still sharks around is that sharks are better at being sharks than anything else is. Physical books are tough, hard to destroy, bath-resistant, solar-operated, feel good in your hand: they are good at being books, and there will always be a place for them. They belong in libraries, just as libraries have already become places you can go to get access to ebooks, and audiobooks and DVDs and web content.

A library is a place that is a repository of information and gives every citizen equal access to it. That includes health information. And mental health information. It’s a community space. It’s a place of safety, a haven from the world. It’s a place with librarians in it. What the libraries of the future will be like is something we should be imagining now.

Literacy is more important than ever it was, in this world of text and email, a world of written information. We need to read and write, we need global citizens who can read comfortably, comprehend what they are reading, understand nuance, and make themselves understood.

Libraries really are the gates to the future. So it is unfortunate that, round the world, we observe local authorities seizing the opportunity to close libraries as an easy way to save money, without realising that they are stealing from the future to pay for today. They are closing the gates that should be open.

According to a recent study by the Organisation for Economic Cooperation and Development, England is the “only country where the oldest age group has higher proficiency in both literacy and numeracy than the youngest group, after other factors, such as gender, socio-economic backgrounds and type of occupations are taken into account”.

Or to put it another way, our children and our grandchildren are less literate and less numerate than we are. They are less able to navigate the world, to understand it to solve problems. They can be more easily lied to and misled, will be less able to change the world in which they find themselves, be less employable. All of these things. And as a country, England will fall behind other developed nations because it will lack a skilled workforce.

Books are the way that we communicate with the dead. The way that we learn lessons from those who are no longer with us, that humanity has built on itself, progressed, made knowledge incremental rather than something that has to be relearned, over and over. There are tales that are older than most countries, tales that have long outlasted the cultures and the buildings in which they were first told.

I think we have responsibilities to the future. Responsibilities and obligations to children, to the adults those children will become, to the world they will find themselves inhabiting. All of us – as readers, as writers, as citizens – have obligations. I thought I’d try and spell out some of these obligations here.

I believe we have an obligation to read for pleasure, in private and in public places. If we read for pleasure, if others see us reading, then we learn, we exercise our imaginations. We show others that reading is a good thing.

We have an obligation to support libraries. To use libraries, to encourage others to use libraries, to protest the closure of libraries. If you do not value libraries then you do not value information or culture or wisdom. You are silencing the voices of the past and you are damaging the future.

We have an obligation to read aloud to our children. To read them things they enjoy. To read to them stories we are already tired of. To do the voices, to make it interesting, and not to stop reading to them just because they learn to read to themselves. Use reading-aloud time as bonding time, as time when no phones are being checked, when the distractions of the world are put aside.

We have an obligation to use the language. To push ourselves: to find out what words mean and how to deploy them, to communicate clearly, to say what we mean. We must not to attempt to freeze language, or to pretend it is a dead thing that must be revered, but we should use it as a living thing, that flows, that borrows words, that allows meanings and pronunciations to change with time.

We writers – and especially writers for children, but all writers – have an obligation to our readers: it’s the obligation to write true things, especially important when we are creating tales of people who do not exist in places that never were – to understand that truth is not in what happens but what it tells us about who we are. Fiction is the lie that tells the truth, after all. We have an obligation not to bore our readers, but to make them need to turn the pages. One of the best cures for a reluctant reader, after all, is a tale they cannot stop themselves from reading. And while we must tell our readers true things and give them weapons and give them armour and pass on whatever wisdom we have gleaned from our short stay on this green world, we have an obligation not to preach, not to lecture, not to force predigested morals and messages down our readers’ throats like adult birds feeding their babies pre-masticated maggots; and we have an obligation never, ever, under any circumstances, to write anything for children that we would not want to read ourselves.

We have an obligation to understand and to acknowledge that as writers for children we are doing important work, because if we mess it up and write dull books that turn children away from reading and from books, we ‘ve lessened our own future and diminished theirs.

We all – adults and children, writers and readers – have an obligation to daydream. We have an obligation to imagine. It is easy to pretend that nobody can change anything, that we are in a world in which society is huge and the individual is less than nothing: an atom in a wall, a grain of rice in a rice field. But the truth is, individuals change their world over and over, individuals make the future, and they do it by imagining that things can be different.

Look around you: I mean it. Pause, for a moment and look around the room that you are in. I’m going to point out something so obvious that it tends to be forgotten. It’s this: that everything you can see, including the walls, was, at some point, imagined. Someone decided it was easier to sit on a chair than on the ground and imagined the chair. Someone had to imagine a way that I could talk to you in London right now without us all getting rained on.This room and the things in it, and all the other things in this building, this city, exist because, over and over and over, people imagined things.

We have an obligation to make things beautiful. Not to leave the world uglier than we found it, not to empty the oceans, not to leave our problems for the next generation. We have an obligation to clean up after ourselves, and not leave our children with a world we’ve shortsightedly messed up, shortchanged, and crippled.

We have an obligation to tell our politicians what we want, to vote against politicians of whatever party who do not understand the value of reading in creating worthwhile citizens, who do not want to act to preserve and protect knowledge and encourage literacy. This is not a matter of party politics. This is a matter of common humanity.

Albert Einstein was asked once how we could make our children intelligent. His reply was both simple and wise. “If you want your children to be intelligent,” he said, “read them fairy tales. If you want them to be more intelligent, read them more fairy tales.” He understood the value of reading, and of imagining. I hope we can give our children a world in which they will read, and be read to, and imagine, and understand.

• This is an edited version of Neil Gaiman‘s lecture for the Reading Agency, delivered on Monday October 14 at the Barbican in London. The Reading Agency’s annual lecture series was initiated in 2012 as a platform for leading writers and thinkers to share original, challenging ideas about reading and libraries.

From the BBC 2013 Dyson Award

http://www.bbc.co.uk/news/technology-24480018

From Dezeen

Ikea to sell flat-pack about time to

News: furniture retail giant Ikea has announced plans to sell flat-packed solar panels.

Ikea’s thin film cells for residential roofs will cost £5700 for 18 panels and – unlike the self-assembly bookcases and sofas the brand is known for – will include installation. The panels are made in Germany by Chinese producer Hanergy Solar.

The scheme will be rolled out to all UK stores in the next ten months, where customers will be able to see the products and have a consultation.

The products are available in the Southampton store on the south coast from Monday following a trial at Ikea Lakeside, east of London, which the company claims sells roughly one photovoltaic system per day.

Ikea has already installed more than 250,000 solar panels on the roofs of its own buildings worldwide.

In July the company used its expertise in flat-pack design to redesign refugee shelters and later the same month it relaunched the first flat-pack table, originally produced 60 years ago.

From Dezeen

Opinion: in his latest column, Sam Jacob argues that hyper-realistic environments created by digital games like The Room give us a new perspective on the history of design.

“I can no longer visit the wine cellar.” Frightening words, but luckily not mine. The phrase comes part of the pretty hokey historic-sci-fi plot that ties together The Room, a BAFTA-award-winning game from British studio Fireproof that has been a smash app on phones around the world.

I wanted to write about it partly because I really liked it. But also because there’s something like Baudrillard writing about Disneyland without going on a ride in writing about “the digital” without really jumping in. You might get the general gist but its real meaning flashes in front of you in a screaming blur while you’re stroking your chin.

The game is set in a series of creepy, dusty, dark half abandoned rooms. But it might be more accurately be titled Furniture as it really centres around a series of strange pieces of furniture. What exactly they are is hard to say. Part desk, bureau, chest, clock, sideboard (and much more) they are nothing so singular. That’s because The Room is really a puzzle, one that comes with it’s questions, riddles, games of skill and observation encoded into fabric of super-hybridised furniture.

To play, you spin yourself around, zoom in and out, push, turn, switch and slide the features you come across on its super-elaborated surface in the hope that something will happen. Doors open, drawers mechanically emerge, mechanisms turn, objects appear, lights switch on. All manner of details emerge. Scraps of paper, photographs, gemstones and fragments of plot are revealed. There’s even (spoiler alert) a maker’s mark: Talisman Co.

Its surface is covered in mahogany marquetry and brass tracery, ceramic inserts and pewter devices – it’s an incredibly dense agglomeration, like the history of design effects 1700-1910 compressed into a single object.

But at the same time its design sensibility seems more Edgware Road than V&A. As though it’s something you might come across in SkyMall, or find in a certain kind of hotel room as one of those complicated teak-tinted hulks that morphs between minibar, wardrobe, TV cabinet, desk, chest of draws and ironing board.

It’s Thomas Chippendale (18th century cabinet maker) and John Harrison (solver of the longitude problem), via Ernő Rubik (the Cube guy) and Hiroshi Yamauchi (Mr Nintendo), with a touch of Daniel Handle (Lemony Snicket), all seen through the lens of Antiques Roadshow. Precisely because of all this a-chronic eclecticism, it’s something utterly of the contemporary moment.

Of course, being an app, it’s all digital. But though it’s just polygons, bitmaps and other representational atmospherics – sheen, shadow and sound effects – it has a tremendous physical presence. Even on the tiny screen of your phone, it feels like a thing.

All of The Room’s suggested tactility somehow seems to jump through the glassy surface of your phone. Turning knobbled keys in creaking locks or as you caress the surface of brass buttons it’s as though your finger is in two places at the same time: both gliding on the super-smooth machined surface of the digital world and dipping into an exaggerated version of the striated physical world. And in this, perhaps we can see something interestingly contradictory that’s happening to how we understand and experience objects.

Your phone’s surface is textureless, the closest we can get to manufacturing a solid version of nothing. Yet the experience it transmits is entirely textured. One is super smooth (and real) and the other entirely textured (but only exists as a representation).

At the same time, the two things are similar. Think of how an app’s code, graphical skin, the data it’s connected to and the interface that organises your engage with it all transform the function and feel of your phone. It’s this fluidity that seems projected into the carpentry and cabinetwork depicted in The Room. As though it’s an object from one world behaving like one from another.

I’d argue that we couldn’t conceive of The Room’s furniture – despite all its olde worlde patina – without thinking of it from the perspective of digital technology. The digital, in other words, is shaping how we see the world and how we expect it to perform. Gadgets, interfaces and apps have opened up other ways of thinking about the things around us, what they might do and how we might use them.

These impossible collisions of technology may not grace the pages of design magazines. Their historicism would rule them out for starters. Yet there are design subcultures that trade in a strange deal across historical boundaries. Not only in the swampy fantasies of Games Workshop, but in Tomb Raider-type special effects and Game of Thrones art direction. In all of these we see images and ideas fictionalising history, reimagining the primitive through cutting edge technologies.

This of course isn’t a new phenomenon. Think of how Sir Walter Scott’s 1820 novel Ivanhoe, set in 12th Century England, kickstarted an craze in medievalism. Think of how the resulting gothic revival gave us that bizarre mix of historicism and technology: St. Pancras and Tower Bridge both serving as examples of clunking infrastructural-historical fantasies. Think too of how this trajectory thrusts us forward towards the Art and Craft politicised revivalism and through into the birth of Modernism. Perhaps it’s possible even to suggest that Modernism’s origins might be filed under historical fantasy romance.

When we try to map the contemporary or the digital into the world we often rely on obvious techniques and translations. Sometimes it wears our algorithms on our sleeve in NURBS based maths built in ways that seem to resist traces of human hands, in order to make it appear as seamless as a model rotating in a Rhino window. Other approaches rely on a kind of over-styled kitsch remake of the futurism we once had.

But I’d argue that it’s exactly the strange hybrids of history and technology that we find a real expression of the contemporary in. I’d argue that this kind of ultra-techno-retro rewires our received narratives of design, suggesting new tendencies and possibilities: fast-forwarding while rewinding at the same time.

This seems entirely appropriate given the way digital culture is transforming culture. It’s certainly changed how we access design. Flattening traditional scholarly hierarchies, breaching what were once secure boundaries between stylistic schools, jumping across chronologies all in a flurry of Google image searches and Pinterest boards. One might add, given the idea of remaking history, that internet culture has accelerated a certain strand of conspiracy theorising that rewrites history with abandon according to highly specific contemporary points of view.

The Room might simply be a game. But in passing it proposes a different resolution between digital and physical things from that usually posited by architecture and design. It’s enhanced textural sensation and dematerialised mutability is as contradictory as it is simultaneous. This formula arranges digitally not as something separate from the world around us (as though it were a 21st century version of Modernism’s tabula rasa) but instead as something present in the world. The digital here is not aestheticised into a stylistic effect but conceived as a lens though which we can view the entire history of design. It becomes a way of re-imagining the relationship between people and things that has unfolded over hundreds of thousands of years, all the way back to the origin of objects when one stone was struck against another to create a sharper edge.

Sam Jacob is a director of architecture practice FAT, professor of architecture at University of Illinois Chicago and director of Night School at the Architectural Association School of Architecture, as well as editing www.strangeharvest.com.

German police test

3D-printed gun

See Dezeen

News: police in Germany plan to 3D print a gun to test whether the weapon can pass through security checks undetected.

According to a report on GigaOM, police officers have bought a 3D printer and will also explore whether printed weapons could be used by the police themselves.

The news emerged in response to a question posed in parliament by Die Linke (The Left Party), the technology website reported.

“The government said the police wanted to see whether ne’er-do-wells could actually make plastic guns that could be smuggled onto planes, and also whether the police might find a use for such technology themselves,” GigaOM said.

The news follows reports that Australian police downloaded and 3D printed their own handgun earlier this year, using materials worth $35. Officers in the Australian state of New South Wales found that the gun fired a bullet 17 centimetres into a standard firing block, but it exploded when it was discharged.

New South Wales police commissioner Andrew Scipione made the announcement at a press conference on 24 May and warned the public about the threat posed by 3D printed weaponry.

“Make no mistake, not only are these things undetectable, untraceable, cheap and easy to make, but they will kill,” said Scipione at the time. Here’s the full speech:

3D printed guns have been making headlines since May 2013, when Cody Wilson, founder of Texas-based Defence Distributed made the CAD designs of a 3D printable handgun available online. The blueprints for the gun, called Liberator, were downloaded over 100,000 times in the two days after they were uploaded to the organisation’s website.

Two days after the first 3D printed plastic gun was successfully fired in Texas, the US Department of Defense Trade Controls removed the files from online public access.

In October last year, open-source design expert Ronen Kadushin warned Dezeen that affordable 3D printers could one day “print ammunition for an army”. He added: “This is a very, very dangerous situation.”

Dezeen has reported on the rise of 3D-printed weaponry in our print-on-demand publication Print Shift, which also looks at how the technology is being adapted to architecture, design, food, fashion and other fields.

Pollution Harvesting

http://www.dezeen.com/2013/06/24/synthetechecology-by-chang-yeob-lee/

3DD printing on the High-Street

http://www.dezeen.com/tag/3d-printing/

The Edible Bus Stop: Community Gardens from Neglected Sites

Repair is Beautiful by Paulo Goldstein

https://www.youtube.com/watch?feature=player_embedded&v=XuGQUKdDeWY

Wind-powered bamboo tumbleweed could clear Afghan minefields (from http://www.wired.co.uk/news/archive/2012-11/22/mine-kafon-bamboo-minesweeper)

Planting landmines is easy and cheap, but the costs (both human and financial) of finding and removing them later can be vast. One possible solution, proposed by Afghan design graduate Massoun Hassadi, is the Mine Kafon. It’s a concept for a wind-powered minesweeper, or an artificial tumbleweed that can — through the serendipity of the wind’s random gusts — clear a blight from the land that kills and maims hundreds each year.

The Mine Kafon looks a bit like a bunch of plungers attached to a central ball. It’s light enough (70kg) to be propelled by a normal breeze, while still being heavy and big enough (190cm in diameter) to activate mines as it rolls over them. When released by its owner, the Kafon will roll around wherever the wind takes it, tracing a path through the sand and able to survive the loss of many of its legs in several explosions before it loses structural integrity.

Wired.co.uk spoke to over the phone to Hassadi in Eindhoven, where he lives after graduating from the city’s Design Academy. The Mine Kafon was his final graduate project, but it’s deeply inspired by his childhood — he grew up on the outskirts of Kabul, in a community where landmine deaths and injuries are common. There are usually hundreds of landmine deaths a year in Afghanistan, thanks to the country’s sad history of conflict over the past few decades.

The Kafon idea came about as part of some “sketches” Hassadi did around the themes of elements — “air, water, fire, the basic elements”, he explains. “I was trying to integrate these, in a physical way. And I also did a project about my childhood in Kabul, where I would make all kinds of things.” Some of those things, as you can see in the video embedded in this story, were toys powered by the wind.

Combining the two ideas led to “12 or 13 toys, or prototypes — one was a helicopter, and another was a sail-powered model”. He spent a couple of months tinkering with designs — and finishing his design internship — before he settled on the current tumbleweed-esque design for the Kafon. Hassadi said: “I worked it up for my final project, and proposed new features and ideas, and we realised that the most interesting was the one that was moved by the wind. It was more personalised, like the toys that we played with in Kabul, outside the house. I was just playing around, and I said ‘maybe I can make one bigger’, as a kind of joke to my tutor, and they said ‘why not?'”

Now that Hassadi has finished his degree he has time to work on the Kafon in earnest. The basic shape and idea is almost there for the first prototype — it has light, strong legs, with feet at the end, and in the middle is a GPS chip. As the Kafon meanders along it transmits data about its journey back to the user. That should allow the plotting of routes through minefields that are safe.

“We’re working on the software now, which is always expensive,” Hassaid said. “So far I’ve been doing the work out of my own pocket, and working with my brother, so now we’re coming up against boundaries. We’re trying to get sponsors, and money, and with that money we can build prototypes that we can send to Afghanistan”.

The centre of the Kafon is modelled on the human body — the ball containing the GPS chip is “level with the knee”, Hassadi explained, because the kinds of mines that it’s designed to clear are the kind that will take a leg off below the knee of an adult. As it rolls around, legs get blown off, but the centre holds.

At the moment, Hassadi estimates the eventual cost of one Mine Kafon will come in at between €40 and €50 (£32 and £40). Currently, he claims, to clear a similar area of mines would cost around $1,200 (£752) using conventional techniques, so the combination of low price and ease of use could drastically improve the the rate at which old minefields are cleared from Afghanistan and other countries blighted by the weapons.

He adds that in the future the plans could be released in an open source format for people to download and adapt to their local situation. The materials on hand might be different, for instance. He said: “It’s not a military project, it’s a humanitarian project. You need to let them help themselves.” FilmmakerCallum Cooper is also producing a short film about the journey of the Kafon from idea to production.

The first goal, though, is to get the Kofan working enough to build a collection to take to Afghanistan and test on the minefields there — and to see what the people living there think of it. And that’s not all, as the this Kofan is just the beginning. Hassadi said: “We also think we can improve it even more — we’ve got ten other designs to try. One of them’s cylindrical, about ten metres wide, and you can steer it as well. There’s no engine, only the air. There’s another that has a wing like an aeroplane.” These designs will be tested as the project continues, subject to backing.

To get the prototypes, though, requires investment, so Hassadi plans on launching a Kickstarter sometime next week (if you want to donate before then, there’s a Paypal donate button on his blog). They’ve deliberately not sought out the help of larger companies or organisations, he says, because “what’s most important is to do it on your own, then it’s possible for everyone — low costs, and low skills”.

Darwins Originals

A short video summarizing some of the most important characteristics of students today – how they learn, what they need to learn, their goals, hopes, dreams, what their lives will be like, and what kinds of changes they will experience in their lifetime. Created by Michael Wesch in collaboration with 200 students at Kansas State University.

Rubbish Duck is a sculpture made from 2000 plastic bottles collected from The Thames and London’s canals.

In many parts of London the canals and rivers are the only high quality public spaces. The waterways are also one of the last natural habitats for wildlife in the city but no organization is in charge of keeping them clean. The waste poses a real threat to birds, fish and other wildlife.

Help us to clean up London’s waterways and build Rubbish Duck sculpture. Follow us and join the Regents Canal clean up on Wednesday 22nd February from 2:00 pm to 4:00 pm!

The event is part of Big Waterways Clean Up 2012 project. All the collected bottles were used to build the Rubbish Duck and here it is!

Sustainable Resources

Online resources

Use the online resources to research inspiring people, projects and places relating to sustainability and to explore how the creative arts and sustainability can be combined.

- Architecture and the Built Environment

- Climate Change, Carbon and the Environment

- Economics and Finance

- Ethics and Fairtrade

- Fashion

- General Sustainability Resources

- Green Jobs and Recruitment

- Higher Education and Sustainability

- Sustainability in Art and Design

- Transport

- Waste, Recycling and Reuse

If you have a resource you think should be included please contact us or add a comment.

Architecture and the Built Environment

- Eco Architects

- Sustainable Architecture

- BREEAM: The Environmental Assessment Method for Buildings Around the World

- The Commission for Architecture and the Built Environment

- Zero Carbon Hub

Climate Change, Carbon and the Environment

- Royal Society Simple Guide to Climate Change controversies

- Cafe Carbon

- Environmental Justice Foundation

- New Scientist: Climate Change: A Guide for the Perplexed

- Energy Saving Trust

- Carbon Trust

- Carbon Footprint

- Water Footprint

Economics and Finance

Ethics and Fair Trade

Fashion

- Slow Fashion

- Interrogating Fashion:

- Centre for Sustainable Fashion

- Fashioning the Future

- Ecouterre

- Estethica

- Source 4 Style

General Sustainability Resources

- TED Talks – Online Lectures ‘Ideas Worth Spreading’

- National Geographic

- DEFRA Environmental Protection resources

- DECC Department for Energy and Climate Change

- Environment Agency

- Envirowise, sustainability advice for business

- Act on CO2

- Institute for Sustainability

Green Jobs and Recruitment

Higher Education and Sustainability

- People and Planet Green League: survey of UK Universities’ environmental performance

- EAUC, The Environmental Association for Universities and Colleges

- HEFCE: Sustainable development in HE resource guide

- The Green Library: A blog site about sustainability in library environments

- Free Radicals

- Brighton University: Inheritable Futures Laboratory

- University of Portsmouth

Sustainability in Art and Design

- HEAcademy list of useful resources

- Sustainable design portal

- Sustainable design network

- Entirely Sustainable Product Design – a good overview of key concepts and tools involved in sustainable design

- The Centre for Sustainable Design

- Ecosustainable HUB – useful links

- Arts and ecology

Transport

- London public transport journey planner

- London travel maps with time planning

- Association for Commuter Transport

- London Air Quality

- Walkit – for planning walking trips. Includes journey times, calories used, CO2 saved, etc.

- Bike Off

- Living Streets – info on walking and improving the walking environment

- London specific version of Living Streets

- Cycle Streets Journey Planner

- TFL London Cycle Routes

- TFL Cycling Information

- Time Out City Cyclist’s Survival Guide

- London Cycling Campaign

- Arts London Cycle Network

Waste: Reuse and Recycle

- Waste Online – useful general info

- Freecycle – pass on your unwanted stuff

- London Remade – recycling within the capital

- Recycle.co.uk – freeycle variant

- Vskips – another freecycle-type resource

- WEEE: Waste Electrical and Electronic Equipment Directive guidelines

- WRAP

RESOUCES: Reading List

Eco publishers: www.earthscan.co.uk Sustainable Design

Birkeland, Dr. J. (2002), Design for Sustainability: A Sourcebook of Integrated Eco‐logical Solutions. London, Earthscan Publications Limited.

Bergman, D. (2010) Sustainable design : a critical guide for architects and interior, lighting, and environmental designers. New York, Princeton Architectural

Black, S. (2008), Eco‐chic: The Fashion Paradox. London, Black Dog Publishing.

Brown, S. (2010) Eco Fashion. Laurence king publishing,

Brower, C. Mallory, R., Ohlman, Z (2009) Experimental eco design. Switzerland, RotoVision

Chapman, J. (2005) Emotionally Durable Design: Objects experiences and identity. London Earthscan

Chapman, J. & Gant, N. (2007) Designers, Visionaries and Other Stories. London: Earthscan. Datschefski, E. (2001) The total Beauty of sustainable products. RotoVision, Switzerland.

Dennis, L. (2010) Green interior design. New York, Allworth Press Dresner, S. (2002), The Principles of Sustainability. London, Earthscan Publications.

Fletcher, K. (2008), Sustainable Fashion and Textiles: Design Journeys. London, Sterling, VA. Earthscan.

Gregson, N., Crewe, L. (2003), Second‐Hand Cultures. Oxford and New York, Berg.

Hethorn, J. Ulasewicz, C. (2008) Sustainable Fashion: Why Now? A conversation ecxploring issues, practices and possibilities. New York, Fairchild Books, Inc.

Jenks, M. (2005) Future forms and design for sustainable cities Oxford : Princeton Architectural. Mackenzie, D. (1991) Green Design: Design for the Environment. Lawrence King

McDonough, W. & Braungart, M. (2002) Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the way we make things. New York: North Point Press Papanek, V. (1985) Design for the Real World. Thames and Hudson, London.

Roberts, J. (2005) Redux : designs that reuse, recycle, and reveal. Layton, Utah, Gibbs Smith Sanders,A., Seager, K (2009) Junky Styling Wardrobe Surgery. London, A&C Black Publishing.

Whitely, N. (1993) Design for Society. Reaktion Books, London MacKenzie, D. (1991) Green Design: Design for the Environment. London, Laurence King PublishingConsumer Culture

Crane, D. (2000) Fashion and its Social Agendas. Chicago; London. Chicago University Press

Hearn, J., Roseneil, S., (1999) Consuming Cultures: Power and Resistance. Basingstoke, Macmillan Hill, J. (2011) The secret life of stuff : a manual for a new material world. London, Vintage Press.

Leonard, A. (2010) The story of stuff : how our obsession with stuff is trashing the planet, our communities, and our health ‐ and a vision for change. London : Constable

Lewis, T., Potter, E. (2011) Ethical consumption : a critical introduction. London, Routledge

Palmer, A.,Clark, H.(2005), Old Clothes, New Looks:Second Hand Fashion. Oxford and New York, Berg.

Pearce, F. (2008), Confessions of an Eco Sinner: Travels to Find Where My Stuff Comes From, London, Eden Project Books.

How we Live

Capra, F. (2004) The hidden connections : a science for sustainable living. New York : Anchor Books,

Carson, R. (1962) Silent Spring. Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Conran, T. (2009) Eco house book London : Conran Octopus, 2009.

Great Britain Ministry of Information (1997) Make Do and Mend. London, Imperial War Museum

Harrison, P. (1993) The third revolution : population, environment and a sustainable world. London, Penguin

Hopkins, R. (2008) The transition handbook : from oil dependency to local resilience. Totnes, Devon, Green Books

Lovelock, J. (2009) The vanishing face of gaia : a final warning. New York : Basic Books

Morris, S. (2007) The new village green : living light, living local, living large. Gabriola, B.C. : New Society Publishers

Petherick, T. (2007) Sufficient : a modern guide to sustainable living. London, Pavilion

Vale, R. (2009) Time to eat the dog : the real guide to sustainable living. London, Thames & Hudson, 2009.

Landfill and waste

Johnson, G. (2010) 1000 ideas for creative reuse : remake, restyle, recycle, renew. Beverly, Mass. Quarry.

McCorquodale, D., Hanaor, C. (2009) Recycle : the essential guide / with an introduction by Lucy Siegle. 2nd ed. London, Black Dog

O’Brien, M. (1999) ‘Rubbish-Power: Towards a Sociology of the Rubbish Society’. In: Pearce, F. (2008), Confessions of an Eco Sinner: Travels to Find Where My Stuff Comes From, London, Eden Project Books.

Marketing and Economics

Anderson, C. (2009) Free: How today’s smartest businesses profit by giving something for nothing. Hyperion, New York.

Anderson, C. (2006), The Long Tail: How Endless Choice is Creating Unlimited Demand. London, Random House.

Bartelmus, P. (1994) Environment, growth and development : the concepts and strategies of sustainability. London, Routledge

Grant, J., (2007), The Green Marketing Manifesto, Hoboken, N.J.: Wiley; Chichester, John Wiley & Sons Ltd.

Hart, K. (2010) The Human Economy. Cambridge, Polity

Hawken, P. (1993), The Ecology of Commerce: How Business Can Save The Planet. London, Weidenfeld & Nicolson.

Hawken, P. Lovins, A.B.& Hunter‐Lovins, L. (1999) Natural Capitalism: The Next Industrial Revolution. London, Earthscan Publications.

McLean, D. “Intergenerational Equity” in White, J. (Ed) (1999) Clobal Climate Change: Linking Energy, Environment, Economy, and Equity. Plenum Press.

Orrell, D. (2010) Economyths : ten ways that economics gets it wrong. London, Icon

![_70402704_revo2[1]](http://www.nickgorse.com/contents/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/70402704_revo21.png)

![dezeen_house-with-slipped-down-facade-Margate-Alex-Chinneck_4[1]](http://www.nickgorse.com/contents/wp-content/uploads/2012/12/dezeen_house-with-slipped-down-facade-Margate-Alex-Chinneck_411.jpg)